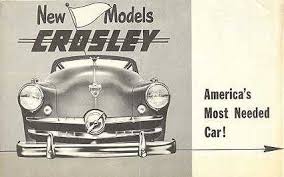

Crosley

As the American automobile grew ever larger during the first decade after World War II, one car maker chose a different path. While the typical Detroit offering of the day tipped the scales at nearly two tons, not a single one of the 75,000 cars and trucks built by the Crosley Motor Company weighed more than a third that amount. Some might argue that Crosley was ahead of its time, pioneering the subcompact car a dozen years before the iconic Volkswagen Beetle. Others might say that its founder, Powell Crosley, was chasing a symbol of the past, the Ford Model T, whose time had come and gone. Whichever way it is remembered, Crosley is a story of what might have been.

The $10 Automobile

Powel Crosley, Jr. (www.crosleyautoclub.com)

The story of the Crosley Motor Company began with a friendly wager between a teenager and his father. In the year 1900, fifteen-year old Powel Crosley, Jr. of Cincinnati, OH, had become taken with an emerging new technology called the automobile. Putting his new-found passion to the test, Powel bet his dad $10 - a week's wage at the turn of the last century - that he could build a car able to travel an entire city block. With funds borrowed from his numbers-wise younger brother, Lewis, the young entrepreneur was able to assemble what he needed; an old buckboard wagon borrowed from his grandfather, a battery obtained from a local theater, and an electric motor of his own design. From these Powel constructed a crude but effective vehicle. With the younger (and lighter) Lewis at the wheel - tiller, actually - the car made its maiden voyage. It went one block from the neighborhood post office and back. With his winnings Powel paid off his suppliers and his brother, and was left with a dollar or so in his pocket, a nice night on the town in those days. He had also acquired a dream that would span a lifetime. The following year Powel graduated from high school, and the Oldsmobile Curved Dash became the first mass produced car. The age of the automobile had begun. Powel Crosley, Jr. was determined to be part of it.

He received sufficient orders for cars to cover the firm's startup costs. With a product and funding in hand, all looked good for the Marathon's late 1907 launch… Until disaster struck. The Panic of 1907 was not unlike our Great Recession a century later. The U.S economy temporarily seized up as banks nation-wide called in loans. Entrepreneurs and businesses went bankrupt by the thousands. Among them was Powell Crosley, Jr.’s Marathon Motor Car Company. His first venture was doomed but the dream endured.

After the Marathon collapse, Powel moved to Indianapolis, a city that at the time rivaled Detroit as a car-making center. He went to work for a large Dayton-Stoddard dealer owned by Carl Fisher. Mr. Fisher, a promoter extraordinaire, was also the driving force behind the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. Powel’s job was prepping new Dayton-Stoddards, delivering them to customers, and making repairs where necessary. He struck up a friendship with Fisher. The latter’s skills as a showman made the Indy 500 a spectacle. They also helped Fisher sell a lot of cars. One of his bolder publicity stunts involved strapping one of his cars to a hot air balloon and flying off, then driving back to Indianapolis 2 hours later to great acclaim.

Carl Fisher christening the Indianapolis Speedway in a Dayton-Stoddard

After three years learning about sales, promotion and publicity from Fisher, not to mention soaking up the atmosphere down at the track, Powell moved on to work for the Parry Automobile Company as their promotions manager. Unfortunately, the Parry Pathfinder was a rather ordinary car that failed to catch on. Meanwhile, Gwendolyn Aiken, Powel’s sweetheart back home, who thus far had been patient though out his adventure, was becoming less so. He returned to Cincinnati to marry her. A daughter soon followed and then a son. There was another brief foray into car making. The 2-seat De Cross Cy-Car was a bit different in that the driver sat behind the passenger. Just one Cy-Car was built before funding dried up. With a family now to support, Crosley put cars aside for a while and concentrated on to the relatively more stable field of advertising.

The Rubber Hits the Road

(RadioMuseum.com)

As Crosley turned his efforts to ad campaigns, the automobile’s impact on the American landscape grew by leaps and bounds. It was now 1916. Nearly a million Ford Model Ts were on the road. The trans-continental Lincoln Highway was complete, opening new places for drivers to go in their Fords. Americans were racking up miles exponentially. These ever-greater distances began to expose the inadequacies of period tire design. Blowouts were common. One of Crosley’s largest advertising clients at the time was Ira Cooper of the Cooper Tire Company. Cooper’s primary business was retreads, worn-out tires capped with lightly used treads. Ira had thousands of old tires and treads ready to be given new life. Many of them, however, were too worn out to reuse. Cooper’s plan was to convert this growing mountain of useless rubber into a new product called tire liners - a kind of patch between the tire and inner tube that would help guard against punctures. Cooper wanted Powel Crosley to develop and promote this new business.

Crosley called this tire-inside-a-tire the Insyde Tyre. He set up a system of franchise dealers to handle sales, which he vigorously promoted. Insyde Tyres were an instant hit. The success led Crosley to convince Cooper to form the American Automobile Accessory Company, one of the first mass aftermarket accessories makers. Before long, Crosley had bought out Cooper, and then brought in his very first partner in the automobile business, his brother Lewis. Powel Crosley could spot growth markets and to create the products to feed them. Lewis got them built cheaply with superior quality. This partnership would participate in another three decades of success.

Powel dreamed up a seemingly endless array of new gadgets for folks to improve and personalize their now million+ Model Ts. There was the Lil Shofur, a devise that helped return steering mechanisms to a straight line, a fuel additive called Kick, and a self-vulcanizing tire patch called Treadkote. As patriotic fervor rose in the build-up to WWI, Powel came up with a flag holder that clamped to radiator caps so that Americans could proudly display Old Glory. They sold, as Powel recalled, “like cool drink in an arid desert.”

(RadioMuseum.com)

By 1919, American Automobile Accessories had sold more than one million dollars-worth of products and the Crosleys were looking to expand into new businesses beyond automobiles. The first was phonographs. These devices cost about $100, at a time when the average working man’s salary was $12 a week. RCA Victor’s patent of the Victrola had recently expired, creating an opportunity. By early 1920 Crosley introduced the Amerinola, a phonograph costing half that of RCA’s machines. Sales quickly took off. The following year, a new rage was sweeping the country: radios. Legend has it, Crosley, at the request of his son, Powel III, walked in to Cincinnati electronic store to inquire as to the price of a new radio. Upon the news that it cost $130, Crosley left instead with a twenty-five cent pamphlet called The ABCs of Radio, along with an idea for his next business venture. Called the Harko, it was more radio for less money than anything on the market. Before long the Crosley Radio Corporation was the largest radio manufacturer in the world. Powell Crosley Jr. became known as the Henry Ford of Radio

Crolsley Field (www.otrmaters.com)

With the radio came the need for programing. To fill that need, Crosley created WLW-AM Cincinnati, which for a time was the most powerful radio station in America. When the Cincinnati Reds baseball club threatened to leave town, the civic-minded Crosley bought the team he’d routed for as a boy, keeping them in the city. Also adding a valuable source of programing for his radio station.

The Crosley bothers used the same strategy that brought such smashing success in radio and phonographs to all their businesses. Powel found products the public wanted, and Lewis found a way to make them both affordable and profitable. “For the masses, not the classes,” was their company mantra. But Crosley’s entry in the refrigerator business was not living up to expectations. While Crosley fridges were cheaper than the completion, they were also smaller and not any better. That all changed in 1933. An inventor walked into Powel’s office to pitch an idea: shelves on the inside of the door. It seems strange today that no one had thought of it before, and downright bazar that the inventor had offered his idea first to GE, Kelvinator and Frigidaire, and all three turned him down. Powel Crosley did not turn him down and the Shelvador was his next big hit.

Throughout his rise to the top, Crosley took on a dozen different industries, dominating several of them. Even the best hitters on his Cincinnati Reds baseball team failed seven out of ten times each trip to the plate. Powel, too, had his strikeouts. Forays into cameras, furnaces and airplanes, were all flops. One of the more embarrassing was the Xervac hair growing device that used vacuum power to suck hair to the surface of barren scalps. It ended up destroying what little hair users already had. But no failure ever came close to threatening the organization. Each time Powel had an idea for a new product he would go to his brother with two questions: What do you think, and how much do we risk before calling it a day? Lewis nearly always answered, yes, because he had the upmost trust in his brother’s instincts, and then he gave a number. The failures never hurt much because any loss incurred was manageable.

Two decades had come and gone since Powel Crosley returned from Indianapolis to sell ads out of a one-room office for $20 a week. His visionary mind, supported by the steady eye of his brother, had placed the Crosleys among America’s greatest industrialists, wealthy beyond wildest dreams. Still, Powel Crosley had one more dream to chase. He still wanted to make cars.

Finally, Cars

One day in 1936, Powel went to his brother with a plan to build an economy car in the Crosley mold, one with a price so low virtually anyone who wanted wheels could have them. He put to Lewis his usual questions about viability and costs and was surprised by his brother’s response. The answers were “no” and “zero”. Crosley was a public company now. They had shareholders to answer to and Lewis felt the automobile was too risky a venture to pursue. Fair enough, Powel would use some of his own considerable fortune to fund Crosley Motors.

Austin Seven

Several years earlier, Powel had purchased an Austin Seven for use at his Florida estate. The Seven was an economy car conceived by Sir Herbert Austin partly in response to Britain’s 1921 horsepower tax – the Seven had very few of those, and was taxed accordingly. The Seven seemed to fit Crosley’s built-for the-masses formula, and was the inspiration for the first Crosley automobile to see production.

1939 Crosley 1A

The Crosley Series 1A was unveiled on April 28, 1939 at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway. The A1 weighed less than 900lbs and measured just 10 feet in length. At $325, the Crosley was the lowest priced car in America, undercutting the equally tiny American Bantam by $62. The Bantam was also inspired by the Austin Seven. The A1 was powered by an air-cooled Waukesha 2-cylinder engine and was offered as either a convertible coupe or a ¼-ton truck.

Immediately after the Indy introduction, the little Crosley’s were shipped off to the New York World’s Fair where they were promoted as “The Car of Tomorrow for the World of Tomorrow.” Crosley did not use traditional car dealers to sell his cars, not with a ready-made network of 25,000 appliance retailers to do the job. The little 1As could be rolled right through the store doors and placed in the showroom next to Shelvador refrigerators and Magna-tune radios.

Crosley 2A Station Wagon

The car was updated in 1940. The new A2 offered two additional versions, a “deluxe” sedan and a maple-bodied station wagon. In one of Powell’s many promotional events, racecar driver Cannonball Baker drover a Crosley A2 cross-country and back on just 130 gallons of fuel. With only 12hp on tap, it is not known how long the journey took.

With its superb fuel economy and minimal usage of raw materials, the A2 would have been just the sort of car America needed as wartime rationing came into effect. So it must have been galling to the Crosleys that the production quotas on automobiles put in place by the government’s War Production Board dictated that just 5757 cars could be built before all civilian manufacture was halted.

The Proximity Fuse

After that, Crosley’s energies turned to war. A few months prior to Pearl Harbor, Lewis Crosley received a call from the Naval Bureau of Ordinance. Crosley Radio had a reputation for the high quality, low cost manufacturing. The Navy sought those attributes in the development and production of a top-secret device called the proximity fuse. With conventional aerial artillery, detonation had to be induced one of three ways: direct contact, a timer set at launch, or by altimeter. Each required tremendous luck in order to down its target. The proximity fuse employed radio signals to tell the ordinance that it is close to its objective and detonate. Referred to as a “force multiplier,” it was said to increase artillery accuracy by eight-fold. Crosley fuses saw their first action off Guadacanal in January 1943 and throughout the Pacific theater. The proximity fuse played such an important role in the ultimate Allied victory, it is considered by war historians to be the 3rdmost significant development of the war, after radar and the A-Bomb.

The Post-War Boom…

Separate from Crosley Industries, little Crosley Motors did its share for the war effort, too, building a variety of less mission-critical items. These included a unique engine that was manufactured from inexpensive and readily available copper-brazed sheet metal. The army, with its love for the acronym, called it the CO-BRA. They were used in a variety machines; generators, pumps, refrigeration units, even a small scout airplane called the Mooney Mite. In Navy tests, the engine ran continuously for 1200 hours without a fault. Once in service, it was proven in combat situations to be extremely reliable.

Powel Crosley and his COBRA engine (CrosleyAutoClub.com)

As an end to hostilities came into sight, Crosley’s post-war attack on the U.S. automobile market commenced. It began with plans for an all-new low-priced car designed around the 4-cylinder COBRA engine. The new car called the Model CC was a bit larger and much more modern than the pre-war A2. The engine’s sheet metal construction made it lightweight and very inexpensive to produce. The overhead cam 26.5hp unit weighted only 133lbs, versus 188lbs for the prewar 12-hp Waukesha.

Despite the COBRA’s advantages, Younger brother Lewis Crosley was not convinced. Originally trained as an engineer, Lewis immediately saw the problems inherent to the COBRA’s design. In time, the water that cooled the steel and copper block would cause oxidation and corrosion. He also felt that it might not be up to the stress of automotive use. Powel, on the other hand, saw the engine as the key to his car’s success. He argued that it had proved itself durable in a variety of combat situations. Guess who won the argument.

Powel proceeded to go all-in on Crosley Motors. He sold his entire business empire to AVCO, a conglomerate that made everything from kitchen ranges to aircraft carriers. Electronics, appliances, the WLW radio station… everything but the Cincinnati Reds; he sold it all to concentrate on cars. His reservations noted, the dutiful, and now very wealthy, Lewis Crosley set about finding a way to make Crosley Motors work.

Powell Crosley with a CC convertible (CrosleyAutoClub.com)

With hostilities over, the race was on to restart civilian production. Starved of new cars for nearly four years, Americans were ravenous. Manufacturers were keen to respond. However, the bureaucrats at the War Production Board where reluctant to yield control of the supply of steel, rubber and other key components. Officials worked out a scheme of allocation based on each auto company’s prewar output. Powel Crosley argued that he should receive a much higher allocation because each of his cars contained far less of the rationed materials than other manufactures. Moreover, they used far less fuel, which was also still rationed. With all the logic and imagination the bureaucratic mind could muster, they turned him down. Thus Crosley was limited to selling less than 5000 cars in 1946 when it could have sold many times that number.

Crosleys on the line (www.carstylecritic.com)

For the first few years after automobile production resumed, most manufacturers peddled warmed over 1942 models. The Crosley was all new and truly different. The CC was a foot shorter than the Volkswagen Beetle that would storm our shores in a few years, and it was half the size of the typical American car. Despite its diminutive dimensions, the Crosley was a masterpiece of space utilization, easily accommodating a pair of 6-footers in front. The 6’4” Powel Crosley insisted upon this. The CC was not only short; it was narrow. This was so that two Crosleys could ride side by side on a standard rail car, thus reducing shipping costs. And speaking of trains, in the July 1947 issue of Mechanics Illustrated, while giving the car overall praise in its review, it was pointed out that the only comfortable way to do 50mph in a Crosley was if it was loaded on a fast moving train.

1948 Crosley steel-body station wagon (www.Cartype.com)

After 4 years of war-time conservation, frugal habits die hard. At a cost of just $888 for a base 2dr sedan, and 44mpg fuel economy, the Crosley auto was just what many post-war buyers wanted. WPB restrictions were eased in 1947 and Crosley production took off. The company built over 19,000 cars that year, earning a net profit of over $475,000. The following year it earned over $800,000 on the sale of more than 29,000 Crosleys. Eight in 10 of those ‘48s were the new all-steel bodied station wagon. Crosley was just the second maker after Willys-Overland to forsake wooden construction for wagons. The Crosley was the number one seller in that category until Plymouth introduced its own steel wagon in 1950. The future looked big for America’s smallest car.

…And then the Bust

From the time civilian production resumed late in 1945, buyers were so hungry for new cars they didn’t care if their purchases were modern. Not so long as the odometer read “000”. For the manufacturers, every car they could build, they could sell. The key to maximum profits was ramping up to full production as soon as possible. The fastest way to do this was just to crank up their pre-war tooling. A new trim piece here and there and voila, a ’42 was now a ’46…and a ’47, and a ‘48. Such was the great post-war seller’s market.

All that changed in 1949. Pent up demand had by then mostly been satiated. Auto sales were returning to where they would normally be. While this ‘normal’ sales level was the highest in two decades, the composition of those sales was changing. The Depression was over. There was no more rationing. Wages were rising, and more and more people joined the workplace. With the affluence that followed, there was a renewed desire for style and flair not seen since the heady days of 1928. Buyers were waking up to the reality that car design had been frozen for seven years. They wanted something new. The big manufacturers were there for them with modern new cars with enticing new features. Consumers began trading in their stodgy pre-war designs for these sleek chromed machines.

This was a problem for Crosley. The primary competitors for the inexpensive CC were used cars, and suddenly those ranks were swelling. Formerly sparse second hand lots now brimmed with trade-ins on the exciting new ‘49s. There was a ready supply of slightly used Fords, Chevys and Plymouths, much larger cars selling for less than a new Crosley.

This shift in the marketplace was a certainly blow to the little carmaker, though by itself not likely a mortal one. Tastes change and smart managements adapt. The Crosley brothers were indeed smart. Powel was adept at finding new markets and coming up with products to fill them, and Lewis could have found a way to make money on 15,000 cars a year. That is what must have made Crosley’s ultimate failure so tough to swallow: It was self-inflicted.

The COBRA engine, light and cheap, so revolutionary that Powel Crosley designed his automobile around it, proved to be the instrument of the company’s destruction. Lewis’ instincts regarding an engine made of sheet metal proved correct. While it performed its wartime duties in generators and airplanes flawlessly, those applications called for operating at a relatively constant speed. This was not the case with an automobile engine, its speed rising and falling as it pulls though the gears. The COBRA engines powering the Crosley CC were now exposed to stresses they had never before encountered. The salt-based anti-freezes that were commonly used at the time, combined with less rigorous maintenance routines of civilians, inflicted further tolls. After a year or two they began to corrode and fail at an alarming rate.

Unreliability from a new manufacturer is a bad omen. For Crosley it was a death-knell. In addition to being a used car alternative, Crosley had aimed the CC at the “second car” market. In those days, second car meant “wife’s car”, and thus there had to be no question of its reliability. A reputation for failing engines doomed the Crosley as a suitable grocery-getter for “the little woman.” (If my wife reading this and now fuming, please remember, my love, this was 1949. You’ve come a long way, baby…)

1949 Crosley CD Convertible Sedan (CrosleyAutoClub.com)

Crosley engineers responded quickly. They replaced the sheet metal engine block early in the 1949 model year with a cast iron one. With a nod to its army roots, it was called CIBA (Cast Iron Block Assembly). The CIBA was installed in an updated Model CD, which looked less gangly, more substantial than the CC. But the damage to the car’s reputation was done. Between the changing market, and the bad publicity of the COBRA, sales for 1949 plunged 75% to just over 7,400.

The (Hot) Shot Heard Round the World

1950 Crosley Hot Shot Super Sport (AutomobileCatalogue.com)

Powel Crosley didn’t give up without a fight. In addition to the CIBA engine and the CD restyle, 1949 also brought an exciting new model. Pre-dating the Chevrolet Corvette by 4 years, the Crosley Hot Shot was America’s first post-war sports car. It had frameless side windows, a one-piece windshield, and frogeye-type headlights - 8 years before the famed Austin-Healey “Frogeye” Sprite. The Hot Shot was based on the CD chassis with a wheelbase stretched 5” for both for better handling and sharper looks. It also was the first modern American car with 4-wheel disc brakes. What The Hot Shot did not have was an abundance of horsepower. The CIBA engine, while durable and rev-happy, produced the same 26.5hp as its disgraced predecessor.

The Hot Shot’s horsepower issue would be addressed quickly. Powel Crosley loved speed and he loved racing. During his years in Indianapolis he tried and failed to hire on as a driver in the first Indy 500. The new-for-1950 Hot Shot Super Sport reflected his passion for the sport in sports cars. It was built to go racing. The Super Sport’s overhead cam CIBA engine was bored out from 720cc to 748cc, and given a higher 10:1 compression ratio. Output rose slightly, and it could now rev to nearly 7,500RPM. These enhancements ware attached to a chassis that while primitive, gripped the road like terrier with a rabbit.

Serious drivers could take their Super Sports to the next level. Available via aftermarket suppliers were hot cams and ignitions, Amal dual side-draft motorcycle carburetors, and a Roots-type supercharger, together boosting horsepower above 60. That doesn’t sound like much, but with the top, doors and passenger seat removed for racing, the Super Sport weighed in at less than 1000lbs.

And racing it went on New Year’s Eve, 1950. The qualities of low weight and tenacious grip served the little Crosley well at Sebring, Florida that day and night. It was the site of America’s first major post-war endurance race, one that would become the internationally acclaimed 12 Hours of Sebring. In those days endurance races were run on European rules, whereby cars were handicapped based on their engine size and whether or not they were supercharged. In this manner, big powerful Ferraris and Allards competed on equal terms with little Fiats and, on this day, a Crosley.

As the story goes, the car wasn’t originally entered in the race. Vic Sharpe, owner of the local Crosley franchise, showed up at the track that morning in a new, mostly stock Hot Shot Super Sport. He ran into a couple friends, Frits Koster and Bobby Deshon The car the two had brought that day was experiencing mechanical troubles that threated to turn them into spectators. After a few practice laps in the Crosley, the two convinced Sharpe to let them “borrow” his car for the rest of the day.

Crosley at Sebring (CrosleyAutoClub.com)

Late to the show and with a big #19 painted on the side, they started 28th out of 28 cars. An experienced enduro racer, Koster realized that downshifting out of turns all day would slowly grind the Hot Shot’s non-synchromesh gearbox into dust. Instead, they chose to just leave the car in top gear and let its superior cornering get them around the track. Going into a curve, the driver would sit up in his seat to let wind resistance slow the car, all the time keeping the engine gunned at 7500RPM. Through the turn he’d slide back down and the little roadster would pick up speed again. After the first hour of racing, the handicap formula showed the #19 Crosley in the lead. For the rest of the race they never trailed.

1963 Honda S500 (ICGD.net)

Hot Shots continued to go racing. A Super Sport won the Grand Pix de la Suisse in 1951. A few weeks later, another placed second in the Tokyo Grand Prix. One easily could imagine that Tokyo competition being witnessed by a young race fan and engineer named Soichiro Honda, who would remember what he saw. Especially when a dozen years later, gazing at Mr. Honda’s first automobile, the feather-weight Honda S500 roadster, and one sees the influence of the Hot Shot.

The true grand prix, the big prize in endurance racing, remained the 24 Hours of Le Mans. Its 1951 running would have one particularly exiguous entry. A couple of amateur racers had taken particular notice of the Crosley’s performance at Sebring. Sportsmen George Schraft and Phil Stiles had always wanted to compete at Le Mans but lacked the funds to be competitive. With the Hot Shot, they saw their opportunity. They wrote to the factory for financial and technical assistance in preparing a car for their campaign. Powel Crosley, a racing fan and always with an eye for promotional opportunities, loved the idea. He had his chief engineer prepare a Super Sport chassis with a specially tuned version of the CIBA engine. With Powell’s backing, Schraft and Stiles brought the car to famed racecar builder, Floyd “Pop” Dryer in Indianapolis to be fitted with a race car body, and have suspension modifications. Then it was off to France.

Le Biplace Torpedo (CrosleyAutoClub.com)

Soon after its arrival at LeMans, the Crosley’s two seats and cylindrical shape earned it the nickname, Le Biplace Torpedo. The trouble for le Torpedo began at the pre-race technical inspection. The Hot Shot’s headlights proved to be too weak for the speeds of the Mulsanne straight and were disallowed. Regulation lights were installed but they required a larger generator. A shipment from the factory wouldn’t arrive by race time, so a French Marchel unit was fitted. This proved the car’s undoing.

The race started at 4PM. For several hours Schraft tore up the course, staying in top gear at close to full throttle. He was steadily moving up through his class, thrilling spectators as he passed more powerful cars in the turns, challenging for the lead. Then darkness fell, the lights came on, and the Marcel alternator began discharging. After a pit and some makeshift repairs, the car went out for a couple of more hours, but the team knew it was over. By midnight, the Crosley was out of the race. The next morning the new generator arrived from Cincinnati.

The poor Le Biplace Torpedo: it was certainly not the first car done in by French technology. There is no telling how the car would have done through the rest of the race had it been able to continue. For Crosley aficionados, the 1951 Circuit de la Sarthe remains the stuff of dreams.

A Last Gasp

The Hot Shot may have been the fastest Crosley of the new decade but it wasn’t the only one. The Farm-O-Road utility vehicle was part pickup truck, part tractor, and it not much larger –or more powerful – than a modern riding lawn mower. It could be fitted with a dump bed, a circler saw for cutting wood in the bush, even front skis, turning it into a snowmobile. Six hundred Farm-O-Roads found buyers.

Crosley Farm-O-Road (CrosleyAutoClub.com)

Crosley's soul lived on. in the late 50s to early 60s the Farm-o-road was reincarnated as the Crofton Bug. Over 200 were sold

The excitement of the Hot Shot and the utility of the Farm-O-Road couldn’t make up for the increasing competition from used cars and damage done by the COBRA fiasco. Sales slid to about 6,800 vehicles in 1950 and 6,600 in 1951. Barely 2,000 Crosleys were built in 1952 before production halted for good on July 3.

French alternators aside, Crosley’s successes in endurance racing make its ultimate failure all the more poignant. The CIBAs durability stood in stark contrast to the COBRA’s fragility. In his book, Crosley (Clerisy Press 2006), author Rusty McClure recounts an exchange between the Crosley brothers as they left their empty car plant for the last time. “The thing that cooked us” said Powel to his brother “was that sheet metal block. If we’d started with cast iron, we might have made it.” He seemed to be acknowledging that Lewis was right about the engine, but wrong about cars.

Who’s to say how things would have turned out for this little maker of little cars? A few short years after Crosley closed its doors, the market would indeed shift back to frugal cars. It is not insignificant that the first Volkswagens did not enter America in any numbers until 1953, the year after Crosley folded. By 1956, they were selling over 40,000 cars, and 400,000 a decade after that. It seems almost heresy to utter this thought, but might the Volkswagen Beetle have never achieved its iconic status in American culture had a thriving Crosley been there to greet it at our shores?

The Volkswagen Beetle (Vector.com)

Sources and Further reading

Crosley: Two Brothers and a Business Empire that Transformed the Nation by Rusty McClure, David Stern and Michael Banks (Clerisy Press 2006) availible at www.oldemilfordpress.com

Dreams Do Come True: The Story of Powell Crosley, Jr., by Edward Jennings and Lewis Crosley (Privately published, date unknown)

The Crosley Legacy, by C.E. Buddy Dyson, Sr. (Jostens, no date)

Powel Crosley, Jr.’s Fertile Mind, by Jim Donnelly. Hemmings Classic Car, November 2013

Too Small, Too Early, by Byron Olsen. Old Cars Weekly, July 11, 2013

Crosley at Le Mans 1951, by unknown. www.classiccartalks.blogspot.com August 20, 2012

Forgotten History: The First Sebring Race. by Barry Seel and Louis Rugani. www.crosleyautoclub.com

Of Super Sports and COBRAs, by Jan Eyerman. www.crosleyautoclub.com