It was 1973, and the future of the sports car looked bleak. A darkness had descended on the world of the automobile enthusiast. The biblical Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse were mounted, and thundering forth to pillage our joy and crush our spirit. Death, represented by the insurance companies, had killed off our beloved muscle cars with prohibitive policy rates. Pestilence, in the form of federal regulators, choked off performance with their emission mandates, and defiled once pretty faces in the name of safety. The oil cartels were a Famine that cut off our fuel supplies. And the social utopians of Conquest, it seemed, sought to ban the automobile completely. The Age of Malaise was upon us.

Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse (www.comicvine.com)

This writer, then just a newly teenaged boy, was despondent. The news from his beloved car magazines was bleak. It told of a new Ford Mustang, the original pony car. It would enter the coming year as nothing more than a tarted-up Pinto. Its most powerful motivation would come from a 109hp six… barely a quarter of the power of 3 short years ago. Over at the financially distraught Chrysler Corporation, termination was deemed cheaper than castration. Its own ponies, the Barracuda and Challenger, were to simply be euthanized. General Motors, at least, had the resources to persevere with its Corvette, Camaro and Firebird. But they were old, fat and wheezing. Big block V8s were on the chopping block everywhere. The American Muscle Car was gasping its last breath. It was looking to this kid caught in pubescent despair, that by the time he finally got his driver’s license in a few years, there would be no more cool cars to drive.

It was then, at this nadir of the modern automobile, did a silver tonged entrepreneur from Florida burst on the scene to save the day. To the stricken car enthusiasts everywhere, Malcolm Bricklin was a super hero. He didn’t have a cape but he did wear a cowboy hat. His super powers were the ability to see - and to sell - the future. Bricklin’s vision: The world’s first safety sports car called the Bricklin SV-1.

Malcolm Bricklin introduces his Bricklin SV-1 (www.howstuffworks.com)

Formerly distraught car geeks poured through the pages of the motor mags in early 1974 as they announced the Bricklin. We lustfully devoured the images, picturing ourselves in place and ready behind that long thrusting hood. Every impulse in the eyes, mind and loins of hormone-charged teenagers told us the SV-1 would be a winner. Suddenly, the future had light.

Indeed, the Bricklin SV-1 would have been a winner; if only young teens were its customer base. Unfortunately, the car’s real clientele was made up of grownups who cared about things like build quality, reliability and price. The real Bricklin automobile turned out to be a hastily developed, poorly constructed collection of tantalizing features that was a lot more pleasurable to look at than it was to own.

The Bricklin Vehicle Corporation built less than 3,000 safety sports cars before the enterprise collapsed. In those two abbreviated years, however, Malcolm Bricklin achieved a lot. He created a company that spanned a continent, and spearheaded a new process for making car bodies. He even managed to bring down a government. Like all the great entrepreneurs of the automobile world, Bricklin possessed the drive and the persuasiveness to see his vision into reality. And, as is often the case with charismatic men, his personality contained the seeds of his vision’s destruction.

Malcolm Bricklin

Malcolm Bricklin’s career began in Orlando, Florida. He dropped out of college after, in his own words, “majoring in time and space.” He set out to pursue his dream of becoming a millionaire by the time he was 25. Bricklin’s father, Albert, ran a successful building supply business in town that he’d built from nothing. Trading on his respected last name, Malcolm sold investors on a new concept, a homeowner-oriented cash and carry hardware franchise called Handyman. It was a local precursor to Home Depot and Lowes. While father Albert had nothing to do with Handyman, local investors assumed that he did, and funded the venture. The chain eventually ran into difficulties and folded.

But not before Bricklin had sold his stake for what he claimed amounted to his $1 million goal.

NYC's finest mounted up (www.thescooterist.com)

Having acquired a taste for The Deal, Bricklin turned his attention to the motor scooter business. The Italian scooter manufacturer, Innocenti, decided it could no longer compete profitably in the U.S. with the hot new Japanese motorcycles. This was the mid-nineteen sixties, the time of Honda’s wildly successful “You Meet the Nicest People on a Honda” ad campaign. Motorcycle sales soared while scooters plunged. Innocenti found itself stuck with a warehouse full of Lambretta scooters with no customers in sight. Enter Mr. Bricklin. Without putting up any of his own money, Malcolm Bricklin managed to convince the New York City police department to buy a substantial portion of those Lambrettas and use them for patrolling Central Park.

On a roll, Bricklin soon after convinced Fuji Heavy Industries of Japan to grant him rights to distribute their Rabbit motor scooters. He set up a franchise system similar to the Handyman stores that had worked out so well for him… if not the franchisees. The venture failed. Americans had come to prefer larger motorcycles like the Honda. Scooters in the States, no matter the nationality, were not going to scoot.

Malcolm Bricklin brought The first Subaru to America (www.oppositelock.kinja.com)

Bricklin was nothing if not a resourceful salesman. Despite the Rabbit failure, he was able to convince Fuji to once again let him be their distributor in America. This time for their Subaru car brand. Bricklin originally had wanted the new Subaru FF-1 Star; a 1000cc sedan he thought could do well in the subcompact market against VW and Datsun. Fuji however, deemed it not worth the hassle and expense of meeting ever-tightening U.S. emission standards. Undaunted, Bricklin reviewed both Subaru’s product line and the Environmental Protection Agency’s rulebook. He discovered a loophole that he could drive a car through - albeit a very small one. Any vehicle weighing less than half a ton was not considered by the EPA to be an automobile. Fuji offered a minicar in Japan called the Subaru 360. This little space bot of a car weighed just 960lbs and thus required no EPA emission certification. Fuji agreed to make Malcolm Bricklin sole U.S. distributor for these first Subarus on American soil.

Bricklin used his now familiar franchise system to recruit dealers. The Subaru 360 was priced at just $1295 - $500 less than a Volkswagen Beetle. This rock-bottom price drew a lot of interest. In the first year of operations, Bricklin and his dealers peddled some two thousand 360s to Americans - presumably small ones - who could now find parking spaces aplenty between 50mpg jaunts.

Things were going swimmingly for Mr. Bricklin’s first venture into the automobile business; that is until Consumer Reports got around to testing one of the tiny cars. They found the motorcycle-engined mini-car to be woefully underpowered. The magazine’s 0-60mph test could only have been conducted while going downhill. This was no surprise. Anyone taking a 90-second test drive in a 360 would have full knowledge of its slug-like performance. The death knoll came when CR simulated a crash between the Subie and a normal sized car. When the 360’s front bumper found its way into the passenger compartment, the testers denounced the vehicles as “unacceptably hazardous” and “the most unsafe car in America.”

(Consumer Union)

Insurance companies immediately stopped issuing policies on the cars. Sales dried up. Fuji Heavy Industries decided it had had had enough of America. But the silver-tonged Bricklin was able to convince them otherwise. If they pulled out now, he reasoned, they would forfeit any future chance at cracking the huge U.S. market. In the end, Fuji did certify the Subaru Star for sale in the U.S. and Malcolm Bricklin got the car he had originally wanted. Well, he almost got it. Fuji also decided to buy Bricklin out of their distribution agreement for, according to him, $20 million.

Subaru FF-1 Star (www.momentcar.Com)

Unfortunately, the buyout did not include taking back the approximately 1,000 now unsalable Subaru 360s gathering dust in lots near their ports of entry.

If one believes in reincarnation, Malcolm Bricklin might have embodied the combined spirits of Indy 500 founder, Carl Fisher, and circus hawker, P.T Barnum. If he couldn’t sell the 360s, he’d race them. Bricklin devised a plan to franchise (there really is one born every minute) local racecourses called FasTracks. For a $25,000 fee, franchisees got signs, fences, lights, helmets and ten Subaru 360 racing cars, now stripped of their glass and trim and sporting racy paint jobs and rubber protective bumpers.

The little Subies didn’t fare much better on the racetrack than they did on the street. Their 2-stoke engines weren’t designed to be flogged around a racecourse by teenaged A.J Foyt want-a-bes. They began to fail at an alarming rate. Moreover, protection bumpers or not, the bodies began to disintegrate from the abuse. Bricklin started to explore the possibility of using fiberglass or acrylic to make replacement bodies. But FasTrack was disintegrating as quickly as the sheet metal on its cars. Bricklin was sued for $2.5 million by franchisees claiming breach of contract, and his interest in the venture waned.

Prototype acrylic-bodied FasTrack racer (The Lane Motor Museum))

Some might argue that the 360/FasTrack adventure was a disaster (especially if you’d owned a franchise.) For the optimist Malcolm Bricklin it was a teachable moment. The Consumer Reports debacle gave him an appreciation for the virtues of safe cars, and through the FasTrack experience he acquired a fascination with acrylic bodies. With these lessons in mind, and some of Subaru’s $20 million still in hand, Bricklin set out to launch a new car like none other; a safety sports car.

The Safety Sports Car

Ralph Nader (Automotive News)

Consumer safety advocate Ralph Nader was inducted into the automobile industry’s Hall of Fame last year for his efforts in bringing automotive safety into public awareness. His seminal work, Unsafe at Any Speed, exposed Detroit’s tendency to put profits before safety. The Chevrolet Corvair, who’s edgy handling characteristics sometimes lead to trouble in the hands of somnobulant drivers, was his exibit A. Nader’s accusations – with an assist from GM and its ham-handed response - brought automotive safety to the forefront of public awareness. The episode resulted in the creation of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration in 1970.

1975 Ford Mustang II: beautiful it aint

At first, sensible mandates where implemented involving shoulder restraints and collapsible steering columns. Then the ever-opportunistic insurance companies got into the act, lobbying the agency to require 5-mph impact-absorbing bumpers. These didn’t do much for safety but they did reduce claims on fender-benders. Soon the bureaucrats were talking about safety cages and airbags. Automakers were scrambling to make their cars compliant …and doing it ever so inelegantly. Malcolm Bricklin sensed his chance to make his idea for a safety sports car a reality.

Under the skin: A hornet with enhancements (www.Bricklinautosports.com)

At the time of the Bricklin SV-1’s conception, the U.S. auto industry consisted of Detroit’s Big Three, along with Kenosha, Wisconsin’s Little One; the smallest carmaker being American Motors Corporation. AMC was always on the lookout for new cash sources, and so was more than happy to supply much of what lies beneath the Bricklin’s exotic skin. The car’s chassis, running gear and most of its suspension bits came directly from the AMC Hornet Hatchback. The same 220hp, 360cid V8 engine from the AMC Javelin found its way into the SV-1’s engine bay. (Tightening emissions rules forced a switch to 175hp Ford V8s in 1975)

It wasn’t all AMC under the surface. The SV-1 was brimming with home grown safety features. Welded directly onto the Hornet chassis were both an integrated roll cage and side impact protection beams. Today these features are federally mandated on all cars sold in America, but in the early seventies this was revolutionary. These features made the Bricklin safer in a crash than any car in America. In a less obvious nod to safety, the SV-1 offered no cigarette lighter or ashtray. Malcolm Bricklin was an avid non-smoker and believed it was unsafe to smoke and drive.

Several different designers took part in the evolution of the SV-1’s look, including Bruce Myers of the Myers Manx dune buggy fame. But it took Herb Grasse, a former Ford and Chrysler designer, to pull it all together. Grasse had a reputation in Detroit for being a maverick. This led him into free-lance design, where he worked with George Barris Kustoms to help create the Batmobile for the 1966 TV series. A maverick himself, Bricklin hired Grasse as his chief of design. This was probably the best decision Mr. Bricklin made during his safety car saga. Even though the SV-1’s plastic body had something of a kit-car look to it, the proportions were excellent. Thanks to the talents of Herb Grasse and his team, the car looked modern and muscular and is still attractive today.

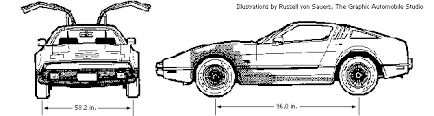

Ah, Those Gullwing Doors

Malcolm Bricklin was a visionary and a salesman all of his adult life. He was masterful in persuading others of the viability of his vision. Now he was the president of an automobile company. Having little experience in the industry, and none at all in manufacturing, some of his visions were proving to be not entirely practical. One of Malcolm Bricklin’s core concepts where that the SV-1 would be a gull-winged sports car. This was among the non-negotiables which Bricklin held his design team. Indeed, those winged doors turned out to be the singular feature for which the car is remembered. However, from the engineers who developed it, to the factory workers who built it, to everyone who has ever owned an SV-1, they were a never-ending source of aggravation.

At the time of its introduction, this was the only production vehicle in automotive history to have powered gull-wing doors that opened and closed at the touch of a button. Grasse had cautioned Bricklin against the doors. Because they closed on two planes, it was nearly impossible to get them to close with a slam fit, which was considered an industry standard. Adding to the difficulty was Malcolm’s requirement that the car have windows that roll down. Non-engineering types, like Mr. Bricklin, would point out that Mercedes-Benz got the doors to work on its 1955 300SLR - and that was twenty years ago! But the Mercedes was a hand built racing car. Its windows didn’t have to roll down. The SLR had no impact beams or interior trim to contend with either. Thus, its doors each weighed only 9lbs. The SV-1’s doors weighed ten times that. The engineers finally solved the problem by using two high-pressure gas struts per door. Before they could fully develop the solution, a new problem appeared. The doors worked but the seals leaked… badly.

Grasse and his team were no doubt capable of solving the engineering challenges. It was those of the human variety that did them in. Their boss, as we may have deduced by now, had a mercurial nature. He would sometimes listen to the most casual suggestion, and decide on a whim he must have it on his car. The engineers had just finished their work on the gas door struts when one of those whims waylaid them.

Someone in Bricklin’s social circle had commented that the car ought to have hydraulic powered doors. The boss went gaga over the idea and insisted the SV-1 now have hydraulic struts. There was not sufficient time or resources to properly de-bug the new hydraulic system before the SV-1 was rushed into production. Owners could almost guarantee failure if they tried to operate the driver and passenger doors at the same time. Between the hydraulic glitches and the faulty seals, getting caught in a heavy rainstorm meant occupants could easily find themselves re-enacting scenes from the WWII submarine movie, Das Boot.

Plastics!

Like Murray Hamilton’s character in the film The Graduate, Malcolm Bricklin became convinced that plastics were the future. Many a maker of niche cars, from the King Midget to the Chevrolet Corvette, turned to fiberglass for their car bodies. The process requires no expensive die casting tools, reducing costs dramatically. The use of fiberglass allows cars to be built in low numbers yet still be profitable. Bricklin learned through his FasTrac research that Acrylics had most of the properties of fiberglass but with the added advantage that they could be molded in the body color. This eliminated the need for the complex and costly factory paint shop, saving even more money. SV-1s would come in one of 5 “safety colors,” chosen for optimum visibility.

Those bodies also turned out to be another source of trouble. Bricklin employed a unique vacuum forming process to bond color-impregnated acrylic to each fiberglass body panel. This was the kind of cutting edge technology he loved to tout. As with the gullwing doors, Malcolm’s ideas were much grander than his company’s resources. Such a manufacturing process had never before been used on a car. The Bricklin engineers were running into difficulties getting the two materials, which possessed slightly differing properties, to stay bonded. But Bricklin was certain the process would work. He had told his investors that it would work, and so it would work.

The bonding process did not work, and it was never fully resolved before production began. Finishes on the early cars was so poor that many buyers, upon seeing the uneven surfaces on their cars, refused delivery. Post-production repair costs swelled.

The Great White North

When one thinks of automobile production, New Brunswick, Canada does not often come to mind. But, in his never-ending search for cash, Malcolm Bricklin found a source by the Bay of Fundy. Richard Hatfield was the premier of New Brunswick. With some gentle and persistent persuasion from a master salesman, Hatfield became convinced that auto production offered a wonderful opportunity to put a major dent in the region’s high unemployment rate. The Premier, in turn, persuaded his provincial parliament to put up what started out as a C$1.2 million loan to get SV-1 production started. The hope was that car production would provide much needed jobs at two idle plants in the vicinity of the city of Saint John. Money, jobs, the scheme seemed like a win-win for everyone, until another unintended consequence revealed itself.

A quick glance at the atlas suggests New Brunswick might be cold. New Brunswick is indeed cold, and this led to yet another unforeseen pitfall for SV-1 production. The Bricklin’s acrylic and fiberglass body panels, already difficult to properly cast and bond, was made doubly challenging by the wet chilly climes of the North Atlantic.

Canada's most famous car (www.arpinphilately.com)

To make matters worse, New Brunswick was not exactly a hub for manufacturing. It did not have an ample supply of skilled factory hands. Much of the pool of available manpower consisted of unemployed fish cannery workers. To go from canning fish to assembling a complex plastic automobile in a climate not suited for casting plastic was quite a leap. Fair to say the leap was a bit too far for the fish canners of New Brunswick. The result was a scrappage rate of 15% for SV-1 body panels, further adding to post production costs and delays.

Of the St Johns experience, Malcolm Bricklin was later quoted in an interview with Car and Driver magazine, “I went where they gave me money, not where the labor was good.”

Money Troubles

The downfall of an independent carmaker nearly always boils down to money, or more specifically, a lack of it. Bricklin Motors was no exception. It has been mentioned here several times that the SV-1 was rushed into production before a number of serious problems could be sorted out. Why would the company bring an unfinished product to market where the customer will almost certainly reject it for its deficiencies? The answer was that delays resulting from the door and body panel problems were making Bricklin’s investors anxious. They were demanding results…meaning sales. The company was operating hand to mouth. If these twitchy investors pulled the plug on funding, Malcolm Bricklin’s house of cards would come tumbling down. So he gave the order to ship the troubled cars to generate sales and get revenues flowing. The problems would have to be fixed later. But by the time ‘later’ arrived, the damage to the SV-1s reputation was done.

Living Hand to Mouth in Canada (www.bricklinMotorsports.com)

Money was also an issue in acquiring components for the cars. Not surprisingly with a manufacturer of Bricklin’s risky nature, suppliers demanded cash on delivery for contracted parts. The company never had the funds to adequately supply its plant and ramp production up to an economical pace. The St Johns factory was expected to be producing 1000 cars a month soon after production began. Between the difficulties producing the body panels and the lack of cash for components, production never came close to those levels. The Bricklin Vehicle Corporation could not build enough cars to generate the revenue to cover operating costs

They All Fall Down

With its inexperienced management, unproven technologies and less than optimal production facilities, the Bricklin Vehicle Corporation was on a collision course with disaster. As it turns out, the point of impact was the parliament building in New Brunswick.

The initial C$1.2 million loan from the provincial government was enough to get the production line set up. But Bricklin had to appeal to premier Richard Hatfield several more times in late 1974 for more funds. This increased the province’s investment to C$7.7 million. The Hatfield government won re-election in January 1975. Malcolm Bricklin congratulated him on his victory, and then promptly asked for yet a further C$7.5 million, which was granted. But apparently, Mr. Hatfield had not informed the parliament of the additional C$6.5 million he had already given Bricklin. A scandal ensued, and the Hatfield government fell.

Out of options, the Bricklin Vehicle Corporation slid into bankruptcy. Just 2854 cars were built over 20 or so months before the company entered receivership. Approximately 35 cars surfaced later, after an automotive liquidator from Columbus, Ohio purchased the majority of the parts and remaining cars left on the line. These cars were assembled and were sold as 1976 models, bringing the total SV-1s produced to 2889.

Those infamous plastic bodies that helped seal the fate of the SV-1 have also done their part in keeping the Bricklin memory alive. Their imperviousness to rust means that, according to the Bricklin International Owners Club, over 1800 still exist today.

Bricklin reunion in St Johns, New Brunswick (www.hamptons.com)

Bricklin after the Bricklin

His namesake car company was no more. But Malcolm Bricklin had been bitten by the automobile bug…or vampire, depending on whether you had purchased one of his cars. The Italian automaker Fiat pulled out of the U.S. market the same year creditors pulled the plug on the Bricklin Vehicle Corporation. Fiat’s sports cars, the X-1/9 and Spider, were still certified for sale in the U.S. Bricklin reached an agreement with Fiat to import and sell them under the names of their respective designers. But the Bertone X-1/9 and Pininfarina Spider were no better cars under Bricklin than they were when they were Fiats. And now there was even less access to parts. The venture soon folded.

After the Fiat sports car rebadging adventure, Malcolm Bricklin set out in search of an economy car he could sell in the U.S. for under $4000. His search led him to Krajujerac, in the Serbian province of Yugoslavia. Here, a government-run factory was pumping out its own rebadged Fiats. In this case it was the 127 hatchback renamed the Zastava Koral. In bringing it to the U.S, Bricklin claimed to have made over 500 modifications to the Koral...including renaming it the Yugo.

(www.yugoinfo.com)

The Yugo was initially popular. But it soon became clear that quality control wasn’t up to western standards. Bricklin claims that as soon as he stimulated demand for the cars, the factory abandoned quality to boost production. In that same Car and Driver interview cited earlier, Bricklin said that the lesson he learned was that, “You can’t take the communist mentality and teach them to maintain good quality.” Whether or not the Yugo ever had good quality to maintain is debatable. Either way, the little car soon became the butt of jokes on late night TV. A guy went to a dealer the other day and said, “I’d like a gas cap for my Yugo.” The dealer thought for a moment and replied, “Okay, that sounds like a fair deal.”

Bricklin halted imports of the Yugo in 1990. The Krajujerac factory was later destroyed, as the nation of Yugoslavia disintegrated into civil war. When the last Yugo was finally unloaded off a lonely dealer’s lot in 1992, it may have been the last car Bricklin would ever sell.

But you never know. As of this writing, he’s still out there, looking for another low priced car to sell through his Visionary Vehicles Corporation. Whether he is yet successful, Malcolm Bricklin will forever be remembered by one formerly disparaged young enthusiast, as a hero who in troubled times gave us hope.

Copyright@2017 Mal Pearson

Sources and Further Reading

Bricklin - H. A. Fredericks with Allan Chambers (1977)

Plastic Fantastic or Gull winged Turkey by Wick Humble. Special Interest Auto, April 1982

1975 Bricklin SV-1, by John F Katz. Autoweek, June 7, 1999

Malcolm Bricklin, by Jim Donnelly. Hemmings Sports & Exotic Car, May 2009

Malcolm Bricklin: What I’d Do Differently, by Steven Cole Smith. Car and Driver, July 2009

The Bricklin International Owners Club. www.Bricklin.org